What Does It Mean To Be Austrian?

Austria is a young nation-state with a brief and tumultuous history and no agreed-upon concept of what constitutes national identity or values

Servus!

Yesterday morning I was at a conference on migration, refugees, and integration in Europe organized by among others the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) and the Forum for Journalism and Media (fjum). Just days prior, European leaders had gathered in Brussels to talk about this very subject, and during negotiations over future funding for additional security at Europe’s common borders, Austria had led a “clutch of countries including Hungary, Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Greece” in “backing tougher border measures,” Politico reported. Immigration, then, is not merely an Austrian national obsession.

Austria, as if I’ve written before, is bound by an immigration paradox. For the past 60 years, Austria has been an Einwanderungsland, a country of immigration. This was true when the first guest workers from Turkey and the former Yugoslavia stepped off the train at the old Südbahnhof and into a new life in a strange land, and became even more evident after 1989 and the collapse of communism in eastern Europe when Austria moved from the continent’s periphery to its center both geographically and economically. As Austrian capital flowed east, labor poured west. On the edge of the western Balkans, the country also became a natural destination for refugees displaced by Slobodan’s Milošević’s wars of aggression in Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Austria, the sociologist and researcher Rainer Bauböck said yesterday, is an Einwanderungsland “in denial.” It needs immigration. Indeed, it is dependent upon immigrants, for without them, critical industries and services from construction to healthcare would collapse, as we almost saw during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 when Europe’s internal borders shuttered and Austria’s care workers were left stranded in their countries-of-origins like Slovakia and Romania. And yet, as essential as migrants are, Austria does not want them. It has one the most restrictive citizenship laws in Europe, declining rates of naturalization, and 1.4 million disenfranchised Austrian residents. Integration remains a word in search of a meaning.

At yesterday’s seminar, fjum’s Mirjana Tomić raised a question that I’ll restate rather crudely. Why is there an American dream but no Austrian dream? Why do people from all over the world come to the United States and so readily identify with their new homeland in a way that immigrants to Austria do not? Now, there is a tendency, as the French migration researcher Patrick Weil rightly noted, to accentuate both America’s achievements and Europe’s failures in this regard. Still, Tomić’s question hit upon feelings of belonging and alienation that are very real and relate in part, I believe, to the fact that Europe and the United States hold to two fundamentally different conceptions of nationhood and the purpose of immigration.

Since the 1960s, the Austrian and European approaches to extra-European migration have tended to be narrow and reactionary: responses to acute labor shortages that have been resolved via the importation of foreign workers without much consideration of vital questions concerning integration1. In Europe, immigrants are a solution to a specific problem rather than a solution in and of themselves. The United States also has labor migration through its various H visa programs, but mechanisms like the Diversity Immigrant Visa are indicative of entirely different mindset, one which sees immigrants as people and not merely as labor. Naïvely put2: if you meet the various criteria and win the Green Card Lottery, you too can have the chance to come to America and become part of the national project by engaging a process of self-reinvention and self-transformation.

Thank you for subscribing to the Vienna Briefing. If you know someone who might also be interested in receiving this newsletter, consider sharing it with them today.

The Vienna Briefing is a free newsletter. If you enjoy and would like to support my work, think about sending me a tip via PayPal. Thank you to all those who have contributed.

The openness of American immigration policy has waxed and waned, it is true, and right now it is hard to ignore a certain coarsening in attitudes on the American right towards immigrants, with rhetoric regarding language, borders, and the so-called Great Replacement coming to mirror that of the European far-right. As far, however, this remains largely a matter of style as opposed to form. As Weil noted, even after Donald Trump’s presidency, both the Diversity Immigrant Visa and the Fourteenth Amendment remain in place. On a very basic level, America does remain a project, as Susan Sontag once said, and if America is a project, then there will always be a chance for people to come and try to complete it.

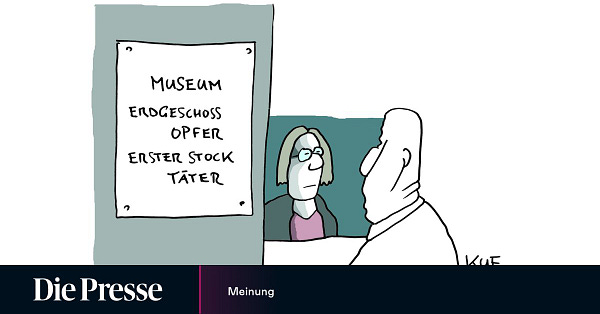

Concerning integration, the United States also has the in-built advantage of being a country founded upon documents and ideas with an accessible and non-exclusionary concepts of citizenship and national identity to which immigrants can easily ascribe. The only European country that comes close to having such things is France, whose identity, Weil argued yesterday, is built on four pillars: the principle of equality; memory of the French revolution; French language and culture; and the separation of religion and state. By stark contrast, Austria can best be described as a young nation-state with a brief and tumultuous history and no clear agreed-upon concept of what constitutes Austrian national identity or values. Anyone can become an American. But what does it mean to be Austrian? Your guess is as good as mine.

Bis bald!

Austria, Bauböck rightly noted, never expected those first guest workers to stay in the country, but rather had the impression they would return to Turkey and Yugoslavia after a few years.

Especially if one considers the original sins of the American republic: those who were displaced to make way for new settlers or had no choice about their arrival in what would become the United States.

Really thoughtful piece, thank you. Austrian identity is publicly still very narrowly projected, clinging to a kitsch 1950s image, despite Austria always having been a multi ethnic, multi linguistic & multi faith state -with a tumultuous history (putting it kindly). To modernise we need to start define 'Austrianess' more inclusively - in reflection of reality, and enforce this inclusivity (e.g. reflect it in public posts, in executive functions) and give people the strategies to deal with this multifacetedness (which isn't always easy). However I have the feeling that people shy away from directly dealing with the topic of national identity (perhaps for good historic reasons) - with the consequence that the discourse of what is and isn't Austrian is mostly left to the right wing.

very good piece — even though I've lived in Austria for a considerable time, I don't see any avenue by which I would be accepted as "Austrian".