Tante Jolesch

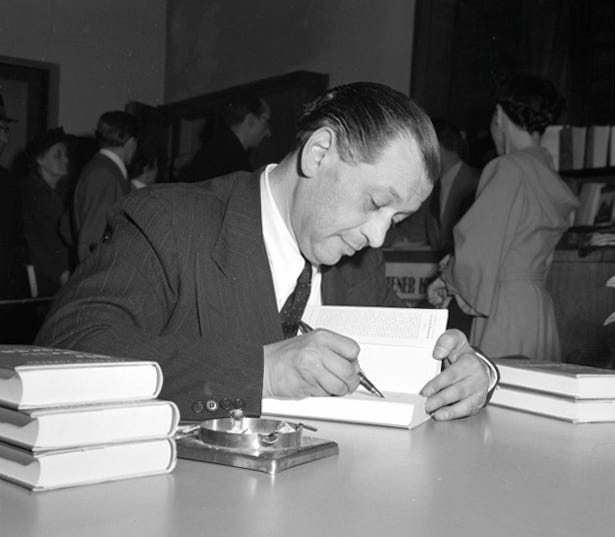

Friedrich Torberg's novel about the lost world of Jewish life in Vienna and Prague between the wars became his most beloved book

Servus!

In 1951, the writer Friedrich Torberg returned from exile in New York and re-engaged himself in Viennese political and cultural life. In 1975, he would write Tante Jolesch or The Decline of the West in Anecdotes, a landmark novel that would become his most beloved work. Moving between Vienna’s coffee houses and summers in Bad Ischl, Torberg conjures a lost world of Jewish life in Vienna and Prague during the period between the wars. Comfortable, middle-class, and assimilated, Torberg’s milieu lived for debate, storytelling, and humor.

Its embodiment and matriarch is Tante Jolesch. Witty, eccentric, and often inexplicable, she was a creature of Vienna with a disdain for travel. “Departures are always precipitous,” she would say. She had an ingrained habit of invoking divine benevolence for a planned event and pointing out the good side of misfortune. A wonderful host, she “cooked exclusively for the enjoyment and comfort of those to whom she served her exquisite creations,” for she had no interest in food herself. Asked of her favorite dish, she would say, “Something ready.”

Tante Jolesch was the “missing link,” Torberg wrote, “between the Talmudic tradition of the ghetto and the emancipated culture of the coffeehouse.” The city’s living rooms, Vienna’s coffeehouses take on an especial importance in Torberg’s mind as the “spiritual home” of the assimilated Viennese Jew, and his book is populated with screwballs and madcaps who practically live there. Take Torberg’s Uncle Hahn. While watching the first film version of The Ten Commandments, he loudly and clearly proclaimed in the silent cinema, “Well, that’s not the way it was at all.”

Another, Ernst Stern—a one-time wrestler attached to the Jewish sporting club Hakoah—was a habitué of Café Herrenhof, where he could be found “either engrossed in lucrative poker games or in Socratic debates.” When the conversation bored or tired him, he would doze off, waking up from time to time to dispense a biting remark. Once, Torberg recalls, Stern strode in to Café de l’Europe, grabbed a piece of apple strudel and devoured it standing up, before announcing: “I hereby demote the Café de l’Europe to a stand-up pastry shop—and I won’t pay.” With that, he turned around and walked out.

Thank you for subscribing to the Vienna Briefing. Every recommendation helps, so if you know someone who might be interested in reading this newsletter, consider sharing it with them today.

The Vienna Briefing is a reader-supported publication made possible by your donations. If you would like to contribute to my work, think about sending me a tip.

That Jews were bound to the coffeehouse shows how interwar Jewish life could be public yet hermetic at the same time. Torberg writes not of the synagogue and the yeshiva but of shops and coffeehouses, bookstores, newspapers, and summer spa towns, and yet the structure and atmosphere of the world about which Torberg writes is unmistakably Jewish. In response to being told that there were 12 million Jews in the world, the writer Egmont Colerus replies, “No way. I myself know more than that.” Such a feeling could only have existed in interwar Vienna when Jews constituted 10 percent of Vienna’s population.

“Many have been drawn to Tante Jolesch for its nostalgic portrayal of a bygone era,” Sonat Birnecker Hart writes in an afterword to its English translation, though to view Torberg’s work purely that way would be to miss the point entirely. Though his work has indeed taken on a kind of nostalgic quality, Tante Jolesch was written out of pain and anguish at a time when Austria had yet to come to terms with its Nazi past. It is not sentimental or wistful but rather melancholic, written against the clock before the “memory-well” from which Torberg drank had gone dry and he had gone the way of all flesh.

Tante Jolesch recalls not only the Vienna of yore but the bitter experience of exile. Torberg understood the world in declinist terms. The erasure of Jewish life in Europe was, as he saw it, inherently linked to the fall of Western civilization: the breaking apart of empires, the rise of nationalism, the collapse of democracy, and finally, war and the Holocaust. Throughout his life, “I always saw something slowly falling apart—something that was dear to me—and I always lived my life under the shadow of decline.” Vienna was losing and would lose something that could not be reclaimed. The Holocaust would leave a void in its culture and society that could not be refilled.

Tante Jolesch, then, is Torberg’s last will and testament—his gift to those who, as a consequence of Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938 and all that followed, were no longer alive to tell their own anecdotes. Dies ist ein Buch der Wehmut, he concludes: “This is a book of melancholy. Maybe I should have written a book of sorrow—but I want to mourn on my own. Melancholy can smile. Sorrow cannot. And smiling is the legacy of my tribe.”

Bis bald!

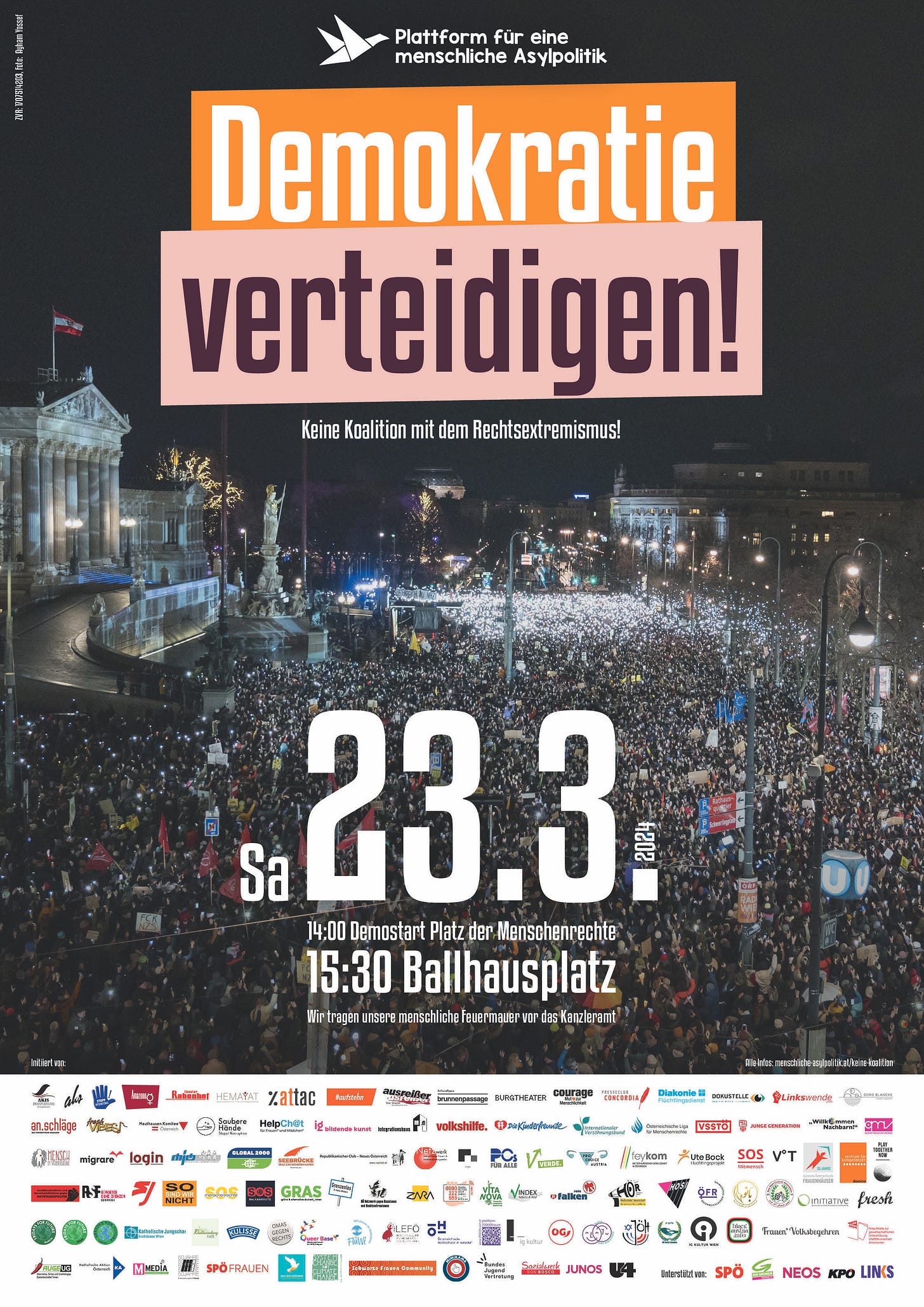

A major demonstration against far-right extremism in Austria—organized by over 120 civil society organizations and supported by five political parties—will take place in Vienna on Saturday, March 23. It will begin at 14:00 on Platz der Menschenrechte (by the Museumsquartier) and culminate with a rally on Ballhausplatz outside the federal chancellery starting at 15:30.

I wrote a lot about Torberg for my dissertation and although his Cold Warrior phase was pretty unpleasant, Tante Jolesch was and remains a marvelous book.

Thanks for this. I'd like the full quote in German if you have it please. I wrote a poem about the memorial X which will appear in one of my next two books with the Theodor Kramer Gesellschaft in English and German. Perhaps it will interest you,