Blue And Yellow Makes Brown

The People's Party has come to a working agreement with the far-right Freedom Party in Lower Austria that allows Johanna Mikl-Leitner to remain governor

Servus!

The unbelievable has come to pass. At the start of February, following regional elections in the state of Lower Austria in which the People’s Party (ÖVP) lost their absolute majority, I wrote to you explaining that “local Freedom Party (FPÖ) leader Udo Landbauer is so extreme” that the ÖVP would never go into coalition with the far-right; it “would be a political disaster.” I failed to take into account, however, that in Austria, things can always be worse, and at the end of last week, Lower Austrian governor Johanna Mikl-Leitner was up on stage with Landbauer, presenting their pact to the assembled press.

Mikl-Leitner started, perhaps, as she means to go on in this next and perhaps final phase of her political life. “I don’t know, based on your accents, if you’re all Lower Austrians here,” she said, which is hardly the best way to ingratiate yourself with a room full of journalists. One could argue, though, that her tone and manner were in-keeping with the theme of her press conference, namely a coalition deal with the FPÖ that places an emphasis on the parochial, the schismatic, and the downright unconstitutional.

Its most disturbing aspect might be the way it brings the FPÖ’s COVID-sceptic politics from the fringes to the center. The deal establishes a €30 million fund “to evaluate the effects of COVID-19 countermeasures” and provide a financial corrective to those who were impacted negatively by them. This will include, the agreement makes clear, people who need “medical care” as a consequence of “vaccine injury,” and the coalition has also committed itself to paying back the fines of those who broke COVID rules. Going forward, Lower Austria will no longer fund public awareness campaigns encouraging people to get the COVID vaccine.

The coalition agreement is a smorgasbord of far-right talking points such as these. The state will no longer use gender-inclusive forms of the German language, for example, adhering itself to the strict male-female binary. German will become the lingua franca of the school playground, in effect prohibiting kids from speaking their native languages among friends on school grounds. The government will give out bonuses to new restaurants that serve “traditional and regional” food. Lower Austrian kebab salesmen need not apply.

Mikl-Leitner is due to be sworn in as governor tomorrow. She had campaigned on the danger of the FPÖ and the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) teaming up to keep the ÖVP out of power; now, she has sold her soul for the sake of power. The FPÖ, meanwhile, promised its voters they would never vote to install Mikl-Leitner as governor. To get around that, the FPÖ plans to abstain when the matter comes up for a vote in the state parliament tomorrow. Time and again, the FPÖ takes its voters for fools.

The ÖVP-FPÖ coalition in Lower Austria sets up a series of possible conflicts between Vienna and St. Pölten. The idea of the state compensating those who were fined for breaking COVID rules would likely be unconstitutional, while other ideas like compulsory German on school grounds is simply unenforceable. At once, it also gives us a glimpse into Austria’s possible future after parliamentary elections are held in 2024. If the FPÖ’s most extreme branch in Lower Austria—a party of “closet Nazis,” as the leader of Vienna’s Jewish community labelled them Sunday—is no longer untouchable for the ÖVP, then neither is the national party.

Bis bald!

Thank you for subscribing to the Vienna Briefing. If you know someone who might also be interested in receiving this newsletter, consider sharing it with them today.

The Vienna Briefing is a free newsletter. If you enjoy and would like to support my work, think about sending me a tip via PayPal. Thank you to all those who have contributed.

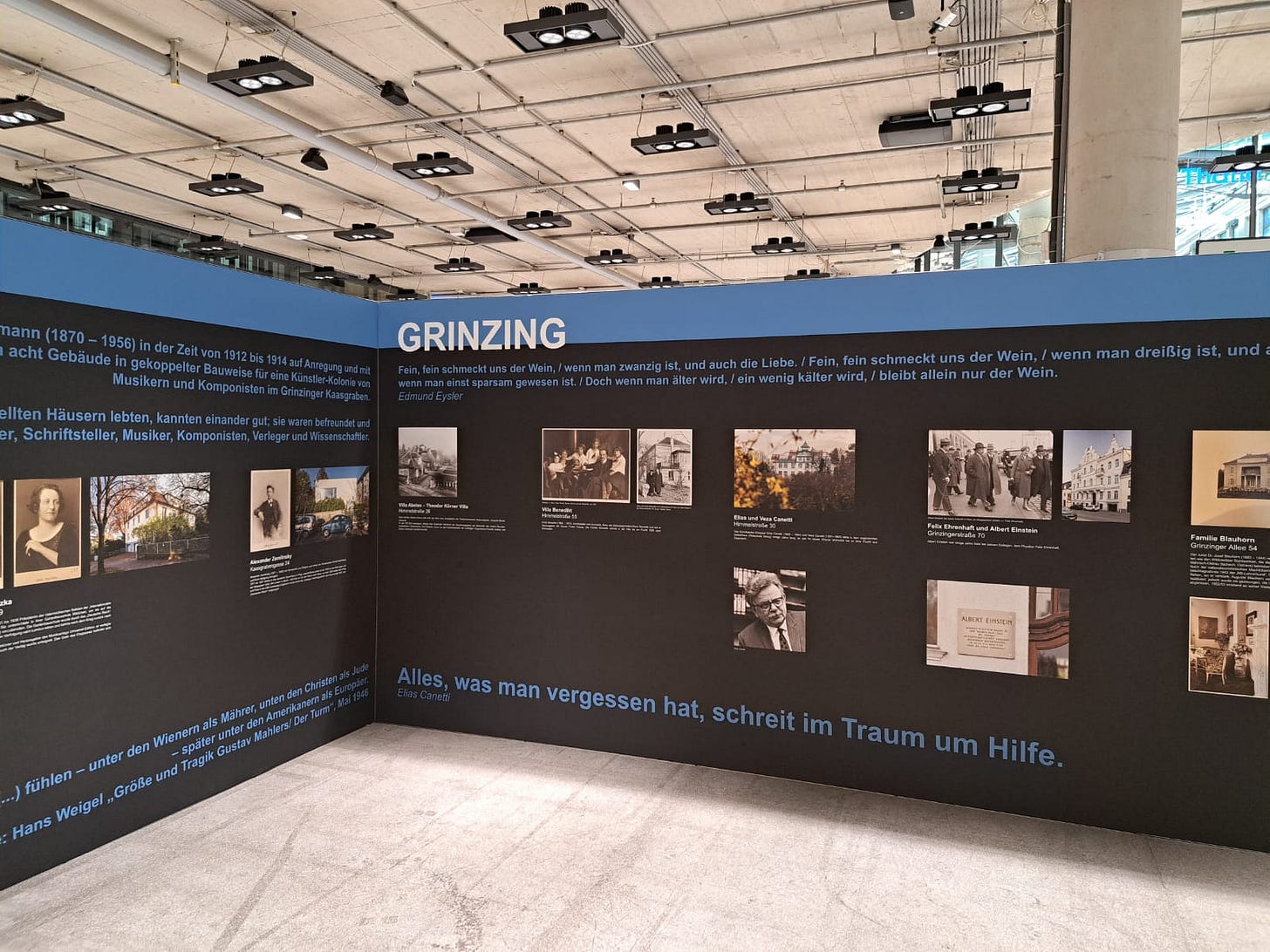

In the second half of the nineteenth century, middle- and upper-middle class Jewish families began to settle in Döbling, Vienna’s nineteenth district, a neighborhood planted with vineyards on the hilly northwest side of the city on the edge of the Vienna Woods.

There, where around 5,700 Jews lived by the early 1930s, Jewish families built villas, opened up parkland, and established institutions like the Rudolfinerhaus hospital, the Institute for the Blind, and the Hohe Warte football stadium. 60 families also lived in the Karl-Marx-Hof, Red Vienna’s landmark social housing project which opened in 1930.

Döbling’s Jewish community was extinguished by the events that followed the Anschluss of March 1938: a tale of expropriation, deportation, and extermination. Now, the memory of that community, their dispossession, and the architectural and institutional legacy they left behind are the subject of an illuminating exhibition currently running at Q19 (Grinzinger Str. 112, 1190; U-Bahn station Heiligenstadt). Check out “Jewish Life in Döbling” before it closes on April 1.