Egon Schiele's Last Years

A new exhibition at Vienna's Leopold Museum shows the expressionist Schiele's artistic maturation during a period of political and personal turmoil

Servus!

On July 28, 1914, one month after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo by members of the separatist, revolutionary Young Bosnia movement, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. That disastrous decision triggered a great war of imperialisms that would sweep the world, drag on for more than four grinding years, and lead to the senseless deaths of around 40 million soldiers and civilians. In the process, Austria would lose its monarchy and its empire, and depart the conflict a poor, withered rump republic that nobody wanted.

1914 was a hinge year, too, for the Austrian expressionist painter Egon Schiele. He was initially deemed unfit for military service, though that decision was overturned one year later, and by mid-1915, Schiele was stationed in Prague. In 1914, he began experimenting with new etching techniques and photographic self-portraits. His sister, Gerti, his first model, married Schiele’s friend and fellow artist Anton Peschka. He became an uncle twice over. And he met the sisters Edith and Adele Harms, the former of whom Schiele would marry in June the following year.

“Changing Times: Egon Schiele's Last Years: 1914–1918,” the comprehensive new exhibition at Vienna’s Leopold Museum, contends that 1914 marks the beginning of the second phase of Schiele’s artistic life. Older, wiser, and in the context of a bloody and mechanized global war, Schiele found, the exhibition seeks to demonstrate, a new point of artistic access. His work from 1914 to 1918 was characterized by calmer, more fluent and organic strokes, more realistic figures, and a greater sense of empathy for his subjects.

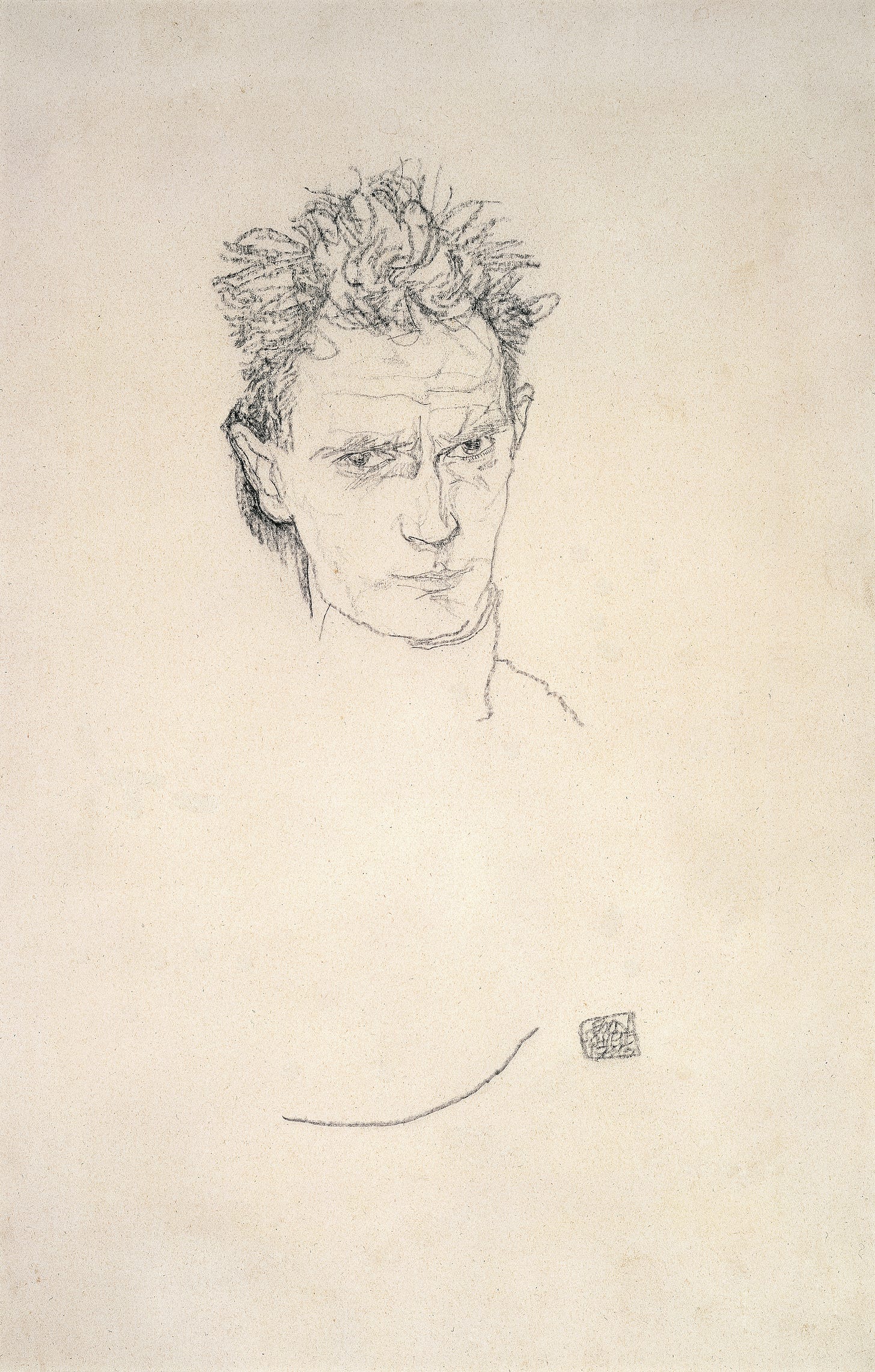

We can see this, first of all, in his self-portraiture. His early work could be excoriating: harsh lines, distorted and almost caricatured features, wizened fingers, missing teeth. Serious, brooding, contemplative, it could also be flattering in the sense that self-portraits flatter the self by placing it at the center of the artistic universe, something which reflected, on Schiele’s part, a condition of self-absorption and egomania. By 1916’s “Self-Portrait in Uniform,” however, we see an attempt at realism and a gentleness and tenderness towards the self that makes Schiele’s earlier self-portrait work seem almost unrecognizable.

Thank you for reading The Vienna Briefing. Nothing beats a personal recommendation; if you know someone who would be interested in reading this newsletter, consider sharing it with them today.

The Vienna Briefing is a reader-supported publication. Your one-time or monthly tips make my work on this newsletter possible and help keep The Vienna Briefing free for everyone.

The same can be said of his paintings and sketches of others, and the best examples of this in “Changing Times” come from Schiele’s life in the army and his depictions of his fellow soldiers and their superiors. There is an empathy present in those portraits that is almost completely absent from his portraits of family members, especially his wife, Edith. In painting after painting, she appears dumpy, sad, melancholic, rigid, lifeless. In “Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Standing” from 1915, Edith looks like a marionette—a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown whose true feelings lie behind her glassy, maddened eyes. There is greater humanity in his portrayal of Russian prisoners of war than his own wife.

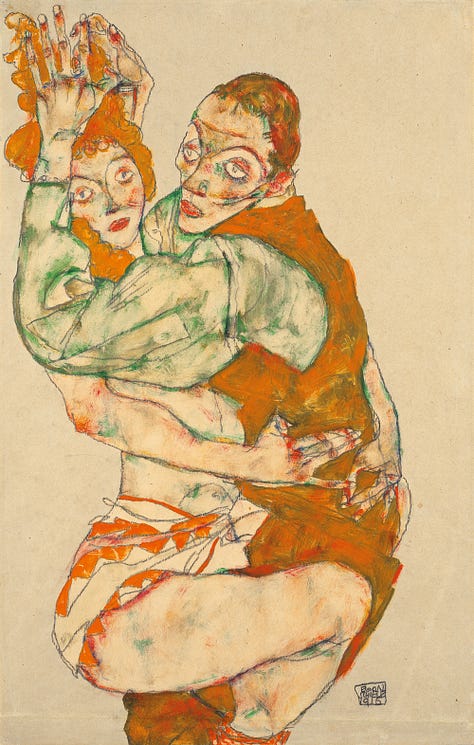

Schiele’s portraiture belies an emotional distance, a coldness, that lay between the artist and his wife. His depictions of physical intimacy, too, indicate feelings of alienation. Whether painting acts of heterosexual or lesbian intimacy, the bodies are physically close but emotionally elsewhere. Heads are turned away from one another, and his subjects’ eyes are painted or sketched as deadened pinpricks. If the eyes are the windows to the soul, there is no point of entry. Schiele’s work on heterosexual or lesbian intimacy, acts of sex and acts of love, perhaps betrays his true feelings on these subjects.

At the beginning of 1917, Schiele’s wife’s father died, and the artist was seconded to the Vienna Imperial and Royal Supply Depot for Officers on Active Service where the director supported Schiele’s work. Back in Vienna, Schiele was able to return to his studio, and his work became evermore preoccupied with the life cycle, especially death and resurrection; Schiele had plans to exhibit friezes in a mausoleum. In February 1918, upon the death of Gustav Klimt, Schiele ascended to the rank of Vienna’s most preeminent living artist. In March, he participated in the organization of that year’s Secession exhibition.

With war’s end but months away, the next phase of Schiele’s career—perhaps a glorious one—was set to begin. The final work in “Changing Times”—1918’s “Portrait of the Painter Albert Paris von Gütersloh”—points to the artist Schiele was becoming. However, just days apart in October 1918, Schiele and his wife, Edith, died of the Spanish flu. On his deathbed, Schiele is supposed to have said: “The war is over, and I must go. My paintings shall be shown in all the world's museums.” The war in fact ended one month later on November 11, 1918. As for the 40 million, the great British war poet Wilfred Owen would ask, “What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?”

“Changing Times: Egon Schiele's Last Years: 1914–1918” runs until July 13.

Bis bald!

Well done. With this piece you've shown us a side of you that we rarely see. Schiele appears to be explicable on the surface but the depth of his creativity is actually difficult to lay out. I tried to do that myself once with his landscapes. The Leopold's exhibit has gotten a lot of press, but few of the pieces attempt to tell us why this period in his life should mean something to us. Schiele, ever the cipher for the modern human, come alive in your letter.

Reading your insightful piece makes me want to hop on the next flight to Vienna! How I’d love to be at the Leopold, one of my favorite museums. Thank you!