Art Against the Status Quo

Debates around Vienna's troubled monuments show the limits of contextualization and possibilities of artistic intervention

Servus!

Operngasse 22-24—a rather plain and unremarkable apartment building in Vienna’s fourth district—was built between the years 1937-1939. Construction was initiated by the Austrofascist Vienna Redevelopment Fund, though by the time the apartment block was done, Vienna had been subsumed into the Nazis’ Greater German Reich. Located on the corner of Faulmanngasse and Operngasse, on the Faulmanngasse side of the building you’ll find its only noteworthy feature: a prominent artistic relief, commissioned under the Nazis and undertaken by the Viennese artist Carl Krall. The relief shows a worker, a peasant, and a manager above the inscription: “The only form of nobility is the nobility of work.”

Under the Nazis, the notion of ‘work’ had a very specific connotation. The relief’s stress on the ‘nobility of work,’ the historian Renée Winter has argued, was part of an attempt to draw a distinction between those who worked and those who didn’t, those who could work and those who couldn’t. Reformulated, this can be seen as a differentiation between those who could contribute to the Nazi state and project and those who were deemed surplus to requirements and worthy of destruction. As such, Winter has said, this dichotomy—and this relief—also has antisemitic connotations.

The Operngasse relief is but one reminder in Vienna of the darkest hours of Austrian history. The centrally-located statue of its former mayor, the political antisemite Karl Lueger, currently represents ground zero in the struggle over history, memory, and memorialization. On the city’s street map, one can still find numerous streets named for composers, scientists, and Olympic athletes who were also Nazi sympathizers or members of the NSDAP. Many of these prominent individuals were honored with streets after the War. And this is to say nothing of the war memorials glorifying the dead of the Second World War to be found the length and breadth of the land.

Thank you for subscribing to the Vienna Briefing. If you know someone who might be interested in reading this newsletter, consider sharing it with them today.

Confronted with the question of what to do with these relics, the City of Vienna has opted for a policy of contextualization, one it believes is the best way to deal actively and critically with the nation’s history. The work of affixing explanatory plaques beneath street signs whose names bear those of Nazis began about a decade ago and is still to be completed. The Lueger monument is due to be made subject to an act of ‘artistic contextualization’ sometime in 2023. And the Operngasse relief will receive some form of additional explanation or contextualization in due course, the city’s culture secretary Veronica Kaup-Hasler announced in December of last year.

The city’s contextualization policy springs from a desire not to turn away from or erase the difficult aspects of Austrian history, which is in one sense admirable. The deficiency in this approach, however, is that it tends to tinker around the edges of a monument or memorial without really touching or altering it. The names of the streets remain, the Lueger monument is still standing, and the relief is due to be kept in place. Even though the intent is to be critical or fashion a more well-rounded image of a person, contextualization ends up being another form of historical preservation that does little to challenge the fundamentals of a street name, monument, or mural.

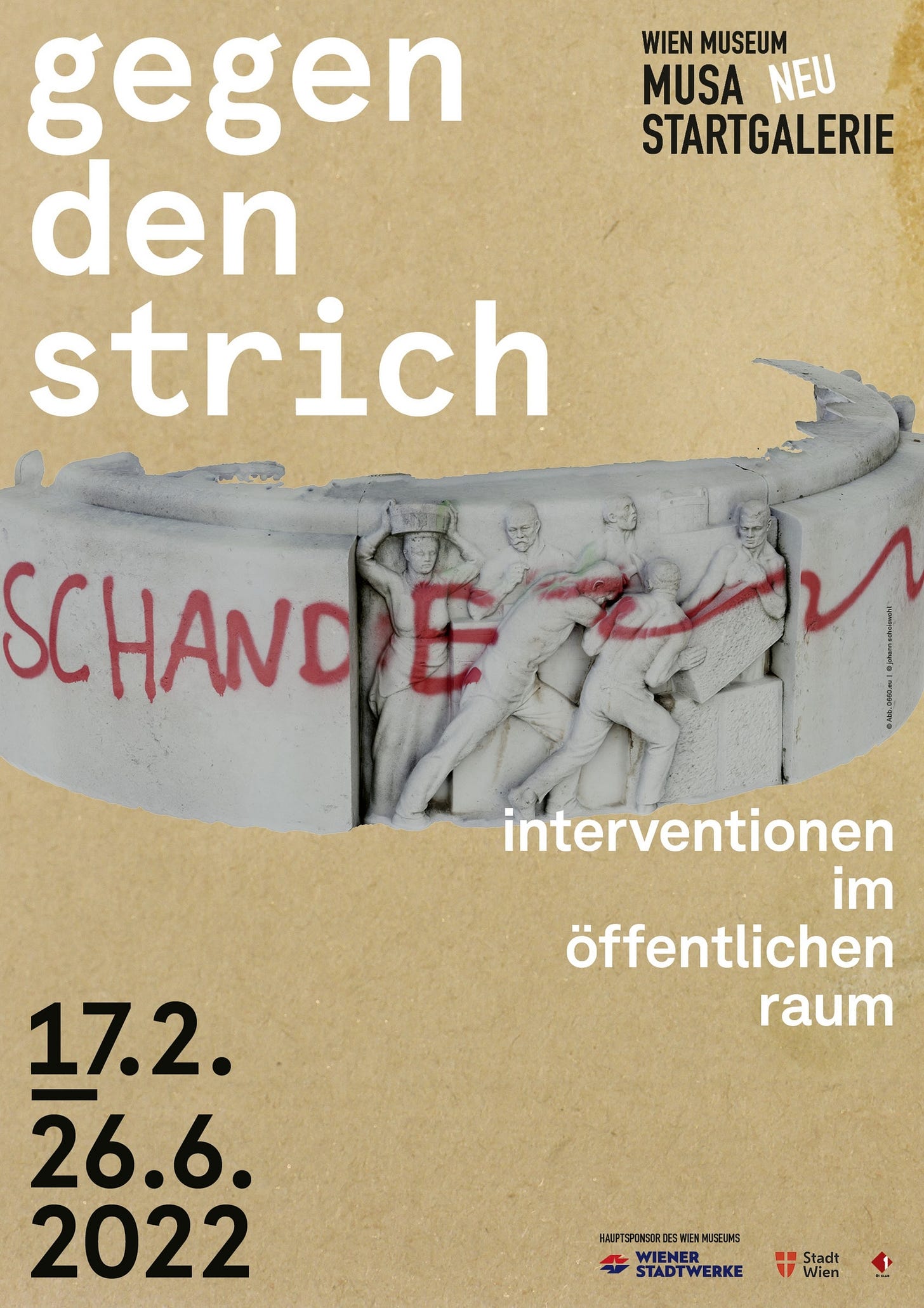

By contrast, a new exhibition at the Wien Museum called “Art Against the Status Quo” shows how artistic intervention can represent a more dynamic approach to dealing with physical manifestations of Austria’s troubled history. The word Schande, shame, which appeared in graffiti on the pedestal of the Lueger monument in the summer of 2020, entirely subverts the meaning of a site designed to honor a world-famous antisemite, stripping it of its honor, demanding that we stop, look at, and consider the man the monument depicts. Finding a way to preserve that graffiti, as the Schandwache collective seeks to do, is one option the city has a duty to consider as it seeks to find a solution for this problem site.

“Art Against the Status Quo: Interventions in Public Space” runs at the Wien Museum MUSA until June 26.

Bis bald!